Our world knowledge and social knowledge is crucial for the production and understanding of discourse.

For effective communication to occur, it is necessary that

– the receiver have enough prior knowledge

– the sender correctly judge the extent of that knowledge

How our pre-existing knowledge of the world shapes the production and understanding of discourse attracted attention mostly due to the advent of Artificial Intelligence – AI.

The most important idea that came into discourse analysis from the field of AI is knowledge schemata.

Schemata are ‘data structure(s) – or networks of stereotypical information about particular topics/themes

The main idea in schemata theory is that the mind, when stimulated by key words/phrases in a particular discourse or by the context, activates existing knowledge schemata and makes sense of the new information by relating it to information already stored.

According to some schemata theorists in the comprehension of (both oral and written) discourse:

– first, a surface representation is attained by breaking down the discourse in to components and stored in the short-term memory and

– next, a mental representation of it is formed in the episodic memory

– finally, a conceptual model is formed and integrated into the long-term memory as scripts or schemata

These three levels of comprehension do not operate independently. Production and comprehension of discourse is helped when linguistic observations activate relevant schemata by focusing on existing knowledge structures (linguistic and world knowledge) larger units of meaning are constructed.

A story for you:

Mahir is often late to school. Today a supervisor asked him why he was late to school so often and he said he didn’t know. According to Mahir, every morning he comes straight to school and yet he is late. So the supervisor asked him to tell her everything he did since he got up until he left for school. And this is what he said:

I got up at 6:30. Got ready. Mum made me a sandwich and a glass of juice. I watched a few minutes of Hendhunu Hendhuna. Then I left for school at about 6:50.

Is this adequate information for the supervisor?

Or would it more appropriate if Mahir had said:

I woke up at about 6:20. I opened my eyes a bit, closed them again and lay in bed for about 10 more minutes. Then I threw back the quilt and sat up cross-legged on the bed. After a few seconds I got out of bed and walked towards the towel rack. I took my towel and walked to the toilet. Then I opened the door and walked in. I took my toothbrush and put some toothpaste on it. Then I brushed my teeth for about a minute or so and rinsed my mouth. Then IÂ … … … After that I put on my uniform … … … and left for school.

When Mahir says he left for school, does he have to tell us that he put on his uniform? Why?

When Mahir tells us that he got up and got ready we assume that he must have got out of bed, cleaned up and changed into school clothes.

This is because we have knowledge of a typical ‘getting ready for school; and can therefore fill in the missing details.

This pre-existing knowledge can be called a ‘getting ready schemata’

When a sender knows that a receiver’s schema to be similar to his own to a significant degree, then he needs to mention only features that are not contained in it (e.g. when he got up, what he had for breakfast etc) and other features (e.g. getting out of bed, putting on the school uniform) will be assumed unless otherwise told.

PROOF OF SCHEMATA

There is much evidence that the mind does use knowledge schemata in interpreting discourse.

One piece of evidence is the fact that when questioned about a particular discourse or asked to recall it, very often we fill in details which were not actually given.

Another piece of evidence is the use of the definite article in certain cases.

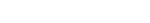

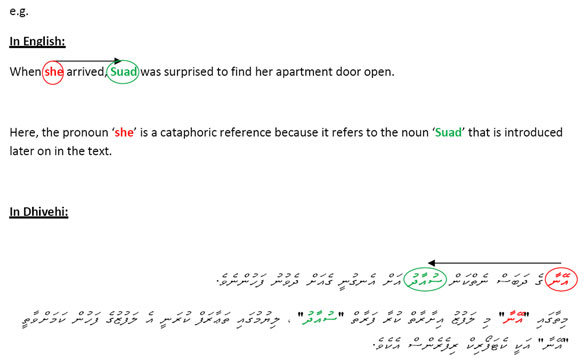

e.g.

As I was already running late I called a taxi. But the taxi driver took so long to find our place that I was late for work anyway.

What is the traditional use of the definite article ‘the’?

So why do we use ‘the taxi driver’ here?

Even though he is mentioned for the first time, it is appropriate to use the taxi driver here because our schemata for ‘taxi’ contains a taxi driver and therefore when someone talks about a taxi coming, we assume that it will have a driver.

However:

As I was already running late I called a taxi. But the TV star took so long to find our place that I was late for work anyway.

If the taxi driver was a TV star, we are unlikely to assume that the listener would know this unless we tell them.

More proof of schemata:

Look at the following and suggest a continuation for each

1. She’s one of those dumb, pretty Marilyn Monroe type blondes. She spends hours looking after her nails. She polishes them every day and keeps them …

2. The king put his seal on the letter. It …

Now look at these continuations:

1. …all neatly arranged in little jam jars in the cellar, graded according to length, on the shelf above the hammers and the electric drills.

2. …waggled its flippers, caught a fish in its mouth.

(Note: these examples are from Cook (1995). They are so interesting and illustrative I had to borrow them!)

Obviously we interpret meanings of words with more than one meaning based on our schemata about the context in which it is used.

This is a method used in jokes, riddles and literature – they activate your existing schemata for a particular topic/context and then overturn it.

Schemata are not simple isolated units stored in the mind that and neither can discourse be interpreted with reference to one schemata.

It is far more complicated than that. In making sense of a piece of discourse, the mind activates a number of schemata simultaneously.

In storing new information any of the following may happen:

– existing schemata are adapted to incorporate new information

– completely new schemata are formed

– old schemata are discarded